Spaulding Adaptive Sports brings news lessons to Nepali, Belarusian leaders

By Brian Canever, Center for Sport, Peace, & Society September 13, 2016Tucked into a corner of the waterfront overlooking the Mystic River and the Boston Harbor, the Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital physically towers over its neighbors in the Charlestown Navy Yard. Consistently ranked among the top 10 rehabilitation facilities in the United States, the hospital is the beacon of Spaulding Rehabilitation Network—a chain of four hospitals and 23 outpatient centers located throughout eastern Massachusetts.

Founded in 1971, Spaulding is at the forefront of innovative treatment for spinal cord injury, traumatic brain injury, and neuromuscular disorders such as multiple sclerosis, cerebral palsy, and Parkinson’s disease. Through its treatment, the organization seeks to address long-term health and function, including reintegrating its patients seamlessly into the community. With physical activity as one of its key means to achieving this goal, the network features Spaulding Adaptive Sports Centers, which serves more than 500 people yearly through programs like adaptive kayaking, canoeing, windsurfing, tennis, bicycling, and wall climbing.

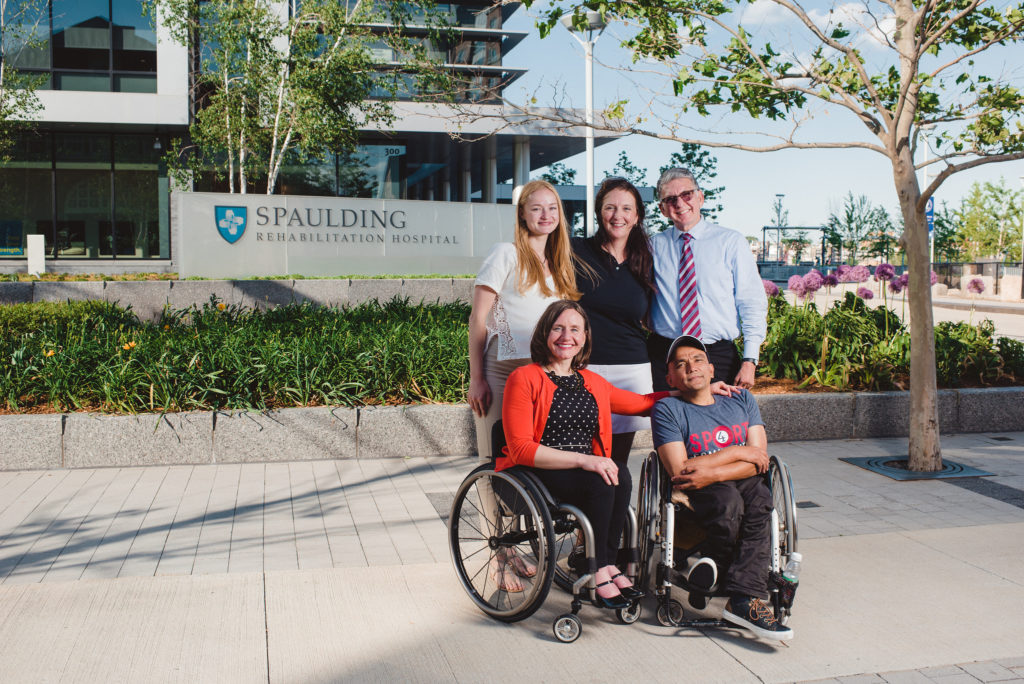

Valeria Filiaeva and Deepak KC stand with their mentors in front of Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital

“Spaulding is at the end of the continuum of healthcare,” said Mary Patstone, director of adaptive sports and recreation. “We seek to use sport as a kind of light that gets our patients through their days. Even if it’s just putting a golf club in their room to see if it’s possible to play. They notice that golf club and they find the motivation to pick it up and push through. Sport gives them a chance to ask the questions: ‘If I can do this, maybe I can make it back to my family, my job, and my community?'”

For three weeks in the spring, Mary and Dr. Cheri Blauwet, an attending physician at Spaulding and three-time Paralympian, served as mentors to two emerging leaders hosted by the organization as a part of the inaugural GSMP: Sport for Community program. Valeria Filiaeva, a wheelchair tennis coach and multimedia journalist from Belarus, and Deepak KC, a universal design architect and deputy secretary general of the Nepal Paralympic Committee, spent time with the two women and others at Spaulding learning how to increase the effectiveness and impact of sport as a tool for rehabilitation and empowerment of people with disabilities in their own communities.

A competitive tennis player until her teens, Valeria traveled the world for competitions and even spent time training at the IMG Academy Bollettieri Tennis Program in Florida. Her transition into coaching wheelchair tennis happened by chance. And despite the challenge of being the first specialized trainer in Belarus, she immersed herself in the sport completely by downloading videos and training materials online, and traveling throughout Europe to learn from more experienced coaches.

“It was a decision that changed my life,” Valeria said. “I didn’t know what I was doing at first. I treated my students like they weren’t disabled. After all, it was tennis. A few years ago, one of my players, an ex-soldier, came up to me and said, ‘I thought you would’ve given up on this after a year. Look at how far we’ve come. Now we have players, courts, tournaments to play in.’ He was proud of me. That helped me realize that this is my destiny.”

In Belarus, Valeria faces a common set of challenges in growing her wheelchair tennis program: lack of accessible transportation and tennis courts, limited financial support, and parents refusing to send their children to learn because they do not understand how sport can improve their lives. Deepak, who uses table tennis to engage people with disabilities in Nepal, shares the same difficulties, on top of attitudinal barriers founded in cultural superstitions of disability as a curse for religious misbehavior.

Valeria sought wisdom from her mentor, Mary Patstone, on how to develop adaptive sports programs

Like their mentor Mary, who managed adaptive sports for Spaulding eight years ago when it was just her driving around a van full of equipment from location to location and volunteering her time with a handful of other helpers, both Valeria and Deepak share an unshakeable commitment to sacrificing their time and abilities to improve their societies. Valeria does it by transferring over her own gifts as a tennis player to what is essentially a volunteer coaching role; Deepak by using his skills as an architect to design accessible facilities for orphanages and other places where people with disabilities live and spend time.

“The first word that comes to mind when I think of Deepak and Valeria is impressive,” said Dr. Cheri, who also serves as the medical chairperson for the International Paralympic Committee. “They’ve already shown their leadership and left their legacy in Nepal and Belarus, working with very few resources. So, the fact that they’ve now gotten a new tool kit of resources, and mentors, and people they can lean on for advice, that is going to empower them to continue using sport for people to access physical fitness and to feel like they’ve been given a voice. I have no doubt their legacy will continue to grow after they leave here.”

Deepak, who was already connected with Dr. Cheri’s husband, Eli Wolff, through the Institute for Human Centered Design in Boston, was deeply affected by the time with his mentors.

“My mentors have been so crucial to me,” Deepak said. “Mary showed me that from the grassroots you can build a program to become great. And Dr. Cheri is a role model and inspiration to me. She is a doctor and a Paralympian. She understands the balance between profession and passion. She has taught me how to find the right balance between my work as an architect and my passion for disability sport.”

The Action Plan developed by Valeria with the assistance of the Spaulding team—Generation Next: Sport for Youth with Disabilities—will include community awareness tennis clinics and improved engagement with local universities and the national tennis federation, with the hope of creating a Paralympic team to compete in the 2020 Tokyo Games. Using another racquet sport as his means to inclusion and empowerment, Deepak will launch EMPOWER Nepal to train table tennis players and create community sports advocates who can then engage locally to increase participation in clinics and community events among people with disabilities.

Deepak, a leader in the Nepali disability sport community, speaks with his mentors outside Spaulding

Understanding the ways that sport can boost confidence, self-esteem, and community engagement, Valeria and Deepak believe they can use this universal language to transform their societies. And part of that change, in the words of Dr. Cheri, is realizing there isn’t that great of a difference between people, regardless of their perceived level of ability.

“You may enter the disability community the moment you’re born or enter into when you’re older, but we all interface with it at some point,” Dr. Cheri said. “Even if it’s transient like a concussion or arthritis, we all face physical challenges. But sport gives you back confidence and control over your destiny. It is an elegant way to reduce the bias that affects how we view people and one of the quickest ways to move past this belief of pity and helplessness when we view disability, and realize that we’re all people in the end.”

View more photos and quotes from our visit to Spaulding to see Deepak, Valeria, Mary, and Dr. Cheri on Facebook (link)